The current resistance represents a collective “no” in the face of Trump’s proposals. In order to bring about positive changes (i.e. those things movements are for rather than simply against) organizers and activists will need to employ a different tool: negotiation.

Some may question whether negotiating with an administration as problematic as Trump’s is even possible, especially given the contentious political environment that is pervasive in the United States today. History provides a good answer in the example of Birmingham, Alabama, and in a situation that was perhaps even more extreme than our own. Fifty-four years ago this week, after a sustained and strategic direct action campaign, black leaders within the civil rights movement sat down with white business leaders and hammered out an agreement to desegregate Birmingham.

In 1963, Birmingham was widely known as “the most segregated place in America,” a place where Jim Crow was in full force. In January of that year, Alabama Gov. George Wallace — a fierce segregationist — delivered his “segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever” speech at his inaugural address.

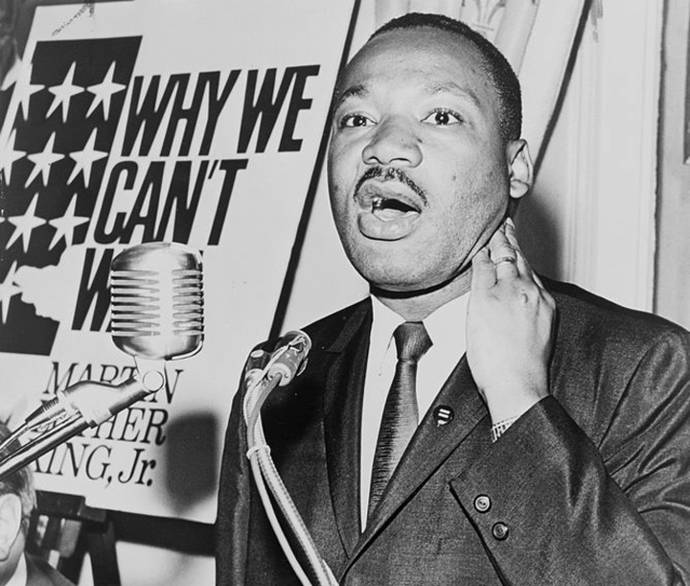

It was in this context that Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, wrote the blueprint for effective nonviolent direct action and — with the help of many others — executed it adeptly with great success. At the core of his strategy were the twin tools of nonviolence and negotiation, and he understood that lasting change was contingent on using both in tandem. As he explained, “The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

King and the SCLC were invited to Birmingham by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, or ACMHR. Not long before, King had led the SCLC in a direct action campaign to desegregate the city of Albany, Georgia with very limited success. He was eager to improve on his strategy and produce results, and Shuttlesworth assured him that there was no better place to do so than Birmingham, stating, “If you come to Birmingham, you will not only gain prestige, but really shake the country. If you win in Birmingham, as Birmingham goes, so goes the nation.”

King took him up on it, and on April 3 the SCLC joined the local ACMHR to begin what would turn out to be a historic campaign. The direct action program was comprised of a number of different tactics, including marches, a boycott of downtown stores, lunch counter sit-ins, and kneel-ins at churches. As a result of these actions, hundreds were arrested, but the campaign continued.

On April 10, the city government obtained a state circuit court injunction against the demonstrations. Running low on funds used to bail protesters out of jail and facing certain arrest if the injunction were to be defied, King had to make the difficult decision about how to proceed. After silently sitting through a meeting with movement leaders, King took a leap of faith.

Knowing the power of symbolic acts, King sacrificially led others in defying the injunction on Good Friday, April 12. In doing so, he also defied the advice of some black business leaders, as well as white clergymen who published a public statement calling the demonstrations “unwise and untimely,” and suggesting that negotiation would be a better route.

King read the statement in his jail cell, and on the margins of the paper began his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” He did not disagree when it came to the utility of negotiation, but he understood that without direct action, power asymmetry would favor the established and unjust power structure, making negotiation for tangible gains impossible. This was one of the major takeaways from his letter, that nonviolent direct action at its best serves as leverage in getting a movement’s representatives to the negotiating table, and in a place where they have the power to make — and win — demands.

Parallel to the direct action campaign, a confidant of King’s by the name of Andrew Young — who would later become the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations — began preliminary negotiations with white business leaders, individuals he was connected to through a contact at the Episcopal Church. He explained what the campaign would entail and the motivations behind their plans. This was strategic, as local and state government officials were unwilling to speak with members of the movement, and because the campaign was largely focused on the business community as a starting point and proxy for wider desegregation.

These leaders had a pragmatic reason for sitting down with Young and his associates: to protect their businesses and bottom lines. Reflecting a Gandhian point of view and seeing the bigger picture, Young said, “I did not view the white business leaders in Birmingham as bad people; they were people in a bad situation.”

This underscores a key lesson for those engaged in a nonviolent campaign, namely that when an opponent won’t deal, costs can be imposed by targeting its “pillars of support,” convincing them — through nonviolent force and negotiation — to redirect their support to the movement itself.

Shortly after King was released from jail, SCLC organizer James Bevel suggested employing an untapped resource in order to sustain the campaign. On May 2, children and youth — who did not face the same work and life constraints as the adults — became the primary protagonists in the direct action campaign.

The next day, Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor led law enforcement in turning the fire hoses and police dogs on these young protesters as they marched downtown. The images that were broadcast shocked the nation and the world. With Birmingham now on the national stage, and tensions at a fever pitch, Attorney Gen. Robert Kennedy sent his chief civil rights assistant, Burke Marshall, to Alabama to facilitate negotiations between black leaders and the white business establishment, building on the foundation Young had cultivated.

In the days that followed the integration of young people into the Birmingham campaign, and with negotiations underway, the Senior Citizens Committee — the formal group representing the city’s white business leadership in negotiations — sought an end to the demonstrations as an act of good faith. King agreed, but noted that they would resume if the situation wasn’t resolved quickly through negotiation.

On May 10, after negotiations that lasted through the night, King, Shuttlesworth, and Ralph Abernathy publicly announced that they had reached a compromise, outlined in what was called the “Birmingham Truce Agreement.” It included the removal of “Whites Only” and “Blacks Only” signs from restrooms and drinking fountains, a plan for the desegregation of lunch counters, a program of upgrading employment for the black community, a biracial committee to monitor the progress of the agreement, and the release of those who had been arrested during the protests.

Direct action had opened the door to negotiation, and through negotiation the movement had brought about concrete gains.

Though progress was made in Birmingham, the response was not universally positive. Segregationists carried out a string of violent attacks, culminating in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, which resulted in the death of four young girls. Additionally, the Senior Citizens Committee, after having played an instrumental role in the negotiations, tried to distance themselves somewhat from the agreement to appease angered whites and segregationist state and local government officials. An article in the New York Times published on May 16, 1963 stated that “The agreement that resulted was worked out by ‘private citizens.’ It involves only private action. It violates no law. It binds no one in the white community except the business involved.”

Still, others almost immediately recognized the importance of the Birmingham campaign. As the New York Times put it, “The agreement is not one that pleased extremists on either side. But it is one that moderate leaders of both the Negro and white communities of Birmingham have said can bring a new era to a troubled city, and perhaps provide a pattern for the whole South.”

The events that took place in Birmingham in 1963 even prompted President Kennedy to deliver a speech on civil rights, which followed King’s cues in framing it as a moral issue that the United States had to get right. The Birmingham campaign and Kennedy’s response to it indeed laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

When nonviolent direct action is used strategically alongside negotiation, the results will often be anything but inconsequential. There is a tendency, however, to see nonviolence and negotiation as mutually exclusive, with activists embracing the former and scholar-practitioners propounding the latter. As King and the Birmingham movement show, far from being opposed to each other, these tools are in fact complementary.

An article from Harvard’s Program on Negotiation puts it this way: “Nonviolent action forces the issues, and negotiation takes the space that is created and gives people a process and tools for discussing the issues in a productive — and nonviolent — way.”

As today’s resistance movement grows and continues to organize, seeking to address the moral issues of our time and bring about positive gains, individuals within it would do well to remember the powerful lesson from Birmingham. Nonviolent direct action is perhaps the most effective way to stand up against the regressive and discriminatory plans of the Trump administration; but lasting change and progress will require holding the negotiation tool in the other hand, and knowing when and where to employ it.

Brandon Jacobsen

Pressenza IPA

Creative Commons

Si (

Si ( No(

No(